Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Theresa M. Evans |

| Original Publication Date: | 15 May 2019 |

| Permalink: |

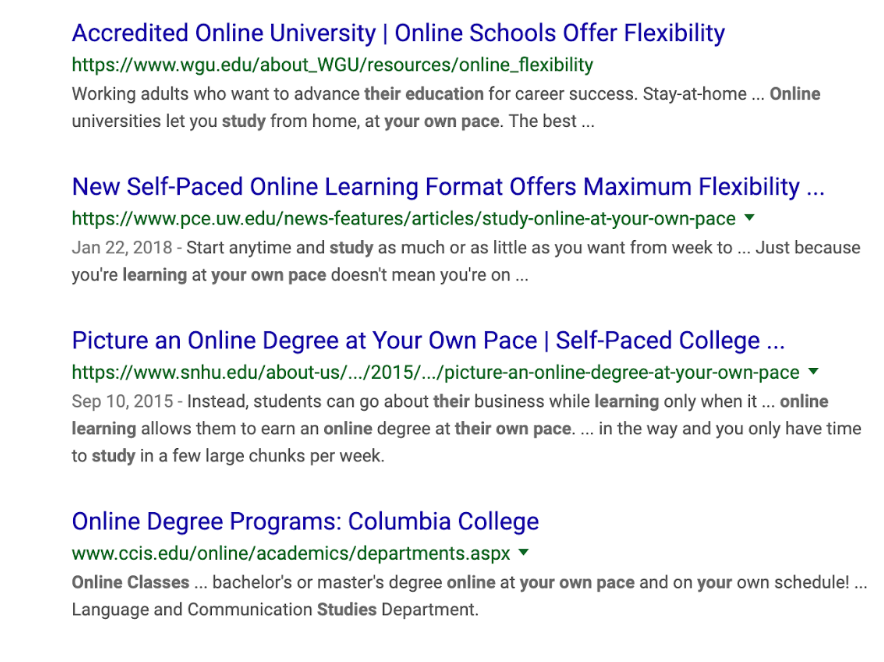

<gsole.org/olor/ep/2019.05.15> |

Abstract

This practice, which addresses OWI Principle 1, is a strategy for managing student expectations for an online writing course prior to the start of the semester and early in the semester. Even if students are capable of doing the work, they might not be able or willing to put in the time required to succeed in a particular online course. The goal is to ensure that students who stay in the course understand how to succeed—or have time to withdraw from the course early enough to avoid receiving a low grade.Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Overview

[1] Managing student expectations means helping students to make informed decisions about registering for, staying in, or withdrawing from an online course. To make those informed decisions, students must understand the parameters of the course, the course platform, and any other technologies used to compose assignments and interact with instructors and peers. Although course content must be accessible, the online course delivery may include schedule, interaction, and technology requirements that some students may prefer to avoid or that interfere with other obligations.

[2] My practice is a strategy for managing student expectations for an online writing course prior to the start of the semester and early in the semester. Even if students are capable of doing the work, they might not be able or willing to put in the time required to succeed in a particular online course. The goal is to ensure that students who stay in the course understand how to succeed—or have time to withdraw from the course early enough to avoid receiving a low grade.

Contextual Details:

A. Type of institution: Four-year research institution

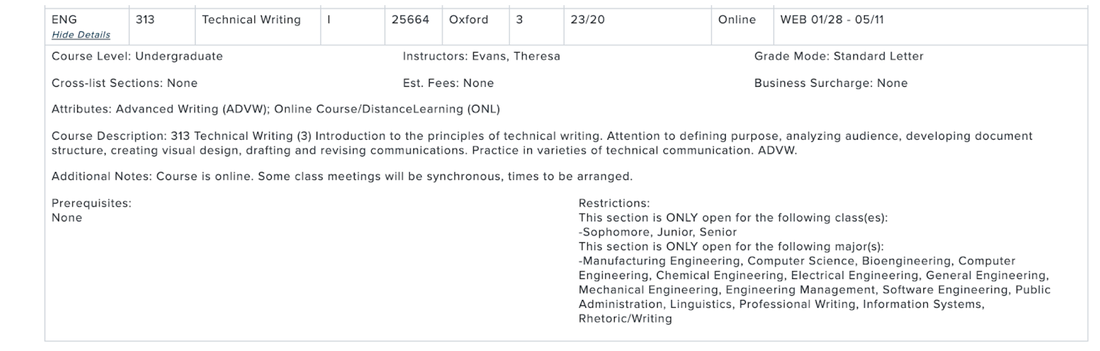

B. Course level(s) and title(s):

- ENG 103: Academic Writing (Ball State University)

- ENG 104: Composing Research (Ball State University)

- ENG 313: Technical Writing (Miami University)

- BUS 284: Professional Communication for Business (Miami University)

C. Course type(s) (asynchronous, synchronous, online, hybrid):

- Asynchronous

- Mostly asynchronous with a synchronous component

- Hybrid

D. Delivery platform(s):

- Blackboard (Ball State University)

- Canvas (Miami University)

2. Provide Clear Parameters of the Course

[3] A wide range of online learning options are possible, so students need a clear understanding of what a particular online course involves. The responsibility for this should not rest solely on the instructor—the university, department, and writing program also have a role. For example, if an online course requires synchronous interaction, that requirement should be transparent at the point of registration, just as face-to-face courses list specific times and days for class meetings.

[4] Institutions sometimes focus too much on the advantages of online instruction when marketing the courses, for example, as offering more convenience for students. The potential consequences of such selling tactics are disgruntled students, who end up with an experience they didn't expect on terms they didn't know they signed up for. Broeckelman-Post & MacArthur (2018) used expectancy violations theory (EVT) to study student expectations of instructors in face-to-face classrooms; they suggested that students are rarely conscious of met expectations, but violations get their attention. Positive violations can enhance the learning environment, while negative violations can distract students from the purpose of their interactions with their instructor (Broeckelman-Post & MacArthur, 2018).

[5] Just a brief Google search reveals that online courses and online degree programs are often marketed as easy, convenient, and self-paced. Students tend to translate those terms as meaning the online course will be less work than the face-to-face course and have no set due dates for assignments. Institutions should clearly define “convenience” as the flexibility to work wherever a student has internet access and to work on most assignments any time of day. Referring to online courses as “self-paced” can be misleading because the more open-ended the schedule, the more self-motivated the student must be to succeed.

[6] Even at my own institution, on the home page of eLearning Miami, a student testimonial states, "Miami makes it easy to take classes online. There’s no hassle”; however, directly below that another message seems to contradict that claim by asking, “Are you ready for online learning? Find out with this short survey.” Marketing messages tend to focus on advantages without clearly defining the terms of the purchase, and students may be buying what they want to believe. Does “easy” and “no hassle” refer to ease of registration—or to easy coursework and a professor who won’t hassle students to get their assignments submitted Helping students understand the expectations for an online course can help improve retention, student motivation, and even the instructor workload. Students who do not understand course expectations create more work for instructors in the form of missed assignments, frustration, and lack of engagement. The labor required to follow up with disengaged students does not directly enhance instruction and also distracts the instructor from actively engaged students.

[7] With a roster of students who are clear about expectations, instructors are less likely to have to spend time reaching out to students whose participation is sporadic or who disappear altogether. Students who understand the unique expectations of their online course are more likely to succeed, and that also creates a more positive learning environment. For high-demand courses, such as required writing courses, managing expectations can help students make better decisions about whether to stay in an online course and can open spaces on the roster for students who might otherwise have been closed out of that particular course section.

3. Focus on the User Experience

[8] Many students tend to be anxious about online courses, especially if they haven’t taken one before. Most express relief when I lay out the scope and ground rules of the course because they often feel overwhelmed.

[9] Managing expectations in any classroom should be focused on reducing student anxiety and establishing rapport. Frisby and Martin (2010) found that instructors’ rapport with students set the tone for learning in the classroom. Webb and Barrett (2014) looked more specifically at how instructors build rapport with undergraduates in the classroom; they suggested that student engagement and participation may be linked to the instructor’s ability to establish positive interpersonal relationships with students.

[10] Establishing rapport online has to be more intentional because there are no spontaneous moments that lead naturally to the kinds of social interactions that build trust and connection. In a study comparing grades in face-to-face classes versus online, Sapp & Simon (2005) found that online courses tended toward a “thrive or dive” (p. 473) environment, where self-motivated students thrive and less-motivated students “dive,” meaning that they withdraw from the course, disappear, or simply fail to participate consistently. Sapp and Simon (2005) suggested that students who performed poorly in online courses needed the structure of regular class meetings and the constant presence of teachers who established rapport with them and motivated them to participate. Although the LMS may send automatic reminders to students, and online instructors can use strategies to create a sense of presence in their courses, not every student is a good candidate for online coursework.

[11] Blair and Monske (2003) have suggested that students and their instructors may or may not benefit from online instruction, depending on how and why technology is used. Reinheimer (2005) found that teaching composition online can take almost twice as much time as teaching face-to-face, with major causes identified roughly as technology, course design, and student learning characteristics. Institutions should ensure that offering the course online serves a real need, that the course is as robust as the on-ground version, and that the course is designed appropriately for the online environment. Student learning characteristics are not usually known to the instructor ahead of time, so the next step would be to communicate what technologies will be used, along with how and why.

[12] The need to read text-heavy instructions, explanations, discussions, and announcements on the online course site may provide an additional challenge for some students. Griffin & Minter (2013) defined “literacy load” as the total amount of reading required for a course, which is significantly higher for an online course, where much of the instruction is delivered through text rather than face-to-face interactions. In a comparison of two first-year writing courses with the same course guidelines, Griffin & Minter (2013) discovered the literacy load of the online version was 2.75 times that of the face-to-face course (p. 153). To help minimize the literacy load, I design my course in ways that reduce clicks and pages and text—and I continually review the course site each semester, looking for ways to shorten and clarify. I also use a short video to walk students through the site, as I explain how and why it is set up the way it is.

[13] Instructors should make sure students understand the LMS, the design of the course site, and the overall scope of the course. Harris and Greer (2018) argued that usability research in the context of online course delivery is not to determine student preferences or instructor likeability; it’s about whether the course site and course design are understandable and user-friendly. The ability to address those challenges early on helps to set the right tone for the course and ensure the rest of the semester runs smoothly.

4. A Three-Pronged Approach

[14] Misunderstandings are often at the heart of unrealistic expectations. Paull & Snart (2016) have suggested that why a student chooses an online course can provide clues to this misunderstanding; for example, when a student does not opt for a face-to-face course he or she might actually be failing to recognize that the online version also requires a time commitment. This basic misunderstanding, which might occur prior to a course even starting, can set the stage for unrealistic expectations, and then subsequent frustration. Advertising for online courses can also create misunderstanding, “since many of the attractive features of online and hybrid learning can be so easily, though often unintentionally, misrepresented and then misunderstood from the student side” (Paull & Snart, 2016, p. 40).

[15] The video below (Video 1) provides a three-pronged approach for addressing misunderstandings and communicating clear expectations for the scope and requirements of an online writing course. These strategies can help improve student retention and create a more positive learning environment for a better user experience.

[16] First, I describe how I manage my own expectations by determining the expectations of my institution and department for delivering the online course.

[17] Next, I discuss my use of pre-emptive communication strategies prior to the start of the online course to help students realign their expectations and enhance retention of those who choose to remain in the course. Not all students will respond to my pre-emptive, pre-start-date email, but I do request that they respond to the email to indicate that they have read it and still plan to stay in the course. After a few days I resend the email to students who have not responded, explaining that students who do not respond to the email or submit the first day’s assignment will be dropped from the course. That second email usually gets results.

[18] Finally, I explain how to set the tone for the course on day one, which can reduce the “bumps and glitches” instructors can expect in an online course no matter how well they plan ahead.

5. Consider Course and Institutional Context

[19] My approach to managing expectations depends on the demand for the course and the reasons some students might want to take it online. If the course is high-demand (i.e., required), then I want to ensure that students who get into the online section understand its requirements relative to the face-to-face version. For example, sometimes students have the expectation that they can get out of group work by taking the course online. The first time I taught the technical writing course online, a few students complained that they thought it was unfair to have a team project in an online course. Since then, I clarify before the course starts that the team project is a requirement of the technical writing course. I suggest that if they are uncomfortable with virtual collaboration, they should take the face-to-face version; however, I also point out that students in the face-to-face class end up doing much of their collaboration virtually. Also, since online students during the regular semester are usually already on campus, they can arrange to have face-to-face meetings with their teams.

[20] All the online courses I have taught have been required undergraduate writing courses with a built-in high demand, meaning there are more students than spaces available. For that reason, my primary goal for managing student expectations is the retention of all students who are still on the roster at the end of the first week of class. If the courses were less in demand, I would probably need to be more accommodating and encouraging to keep them on the roster through that first week.

[21] Once the course starts, my tone shifts to more positive and encouraging. Other ways to manage expectations for online courses from a positive stance include the following:

6. Generate Excitement among Faculty

[22] We have a cohort of instructors for a business communication course, which is offered in an online version twice a year, and is delivered by interdisciplinary instructors. Part of setting expectations for the faster-paced timeframe of the online course involves a pre-semester meeting, a listserv, shared master course template, and a shared folder. Those of us who have taught the class before can offer advice and share class activities with new instructors, and we all converse regularly via our listserv to share ideas and to ask questions of the group. These activities get everyone up to speed faster, foster good collegial relationships, and help us feel less isolated when trying to address particular issues that crop up during the semester. Rodrigo & Ramirez (2017) have reported on the advantages of a master course using Spinuzzi’s (2005) participatory design, noting that this method allows for curricular and professional development to happen simultaneously.

7. Generate Excitement among Students

[23] The best way, in my opinion, to generate excitement among students is to make clear that I am accessible to them and to project a friendly attitude. They are often feeling isolated on their end, so it means a lot to make clear that I am a real person they can interact with and to provide assignments that allow them to interact with their peers. I create some friendly, encouraging, short (1-to-3 minute) videos to introduce myself and to briefly introduce each segment of the course in a way that helps students to see the scope of the course and to put them at ease. Having students introduce themselves through a short video can also be useful, so they can see each other and also practice some of the oral presentation and technical skills they'll be working on during the course.

[24] Students appreciate timely responses to their emails with an attitude of encouragement--especially if they are frustrated or confused about something. I thank them for bringing any issues to my attention and sometimes address those with the class (because, after all, if one person is confused, probably other students are, too!). I encourage students to alert me to anything not working on their end, suggestions for how something could work better, or any technology issues they are having with their projects. One way to do this is through an ongoing FAQ Discussion board that allows students to post questions; this is especially helpful as an early low-stakes assignment to prompt questions and concerns about the syllabus and course site.

[25] Another way I try to generate excitement is by doing some of the projects myself so that I am better able to help them with theirs, empathize with their struggles, and provide an example of what I'm looking for. For example, the business communication class requires a professional introduction video, so I created my instructor introduction video to align with that project. In other words, I try to emphasize that we're all going to have some bumps and glitches, and that's okay! We'll work it out or work around it!

8. References

Blair, K. L. & Monske, E. A. (2003). Cui bono?: Revisiting the promises and perils of online learning. Computers & Composition, 20(4), 441-453. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2003.08.016

Broeckelman-Post, M. A. & MacArthur, B. L. (2018). Are we violating student expectations?Availability, workload, class time use, and technology policies in undergraduate courses. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator, 73(4), 439-453. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1077695817736687

Frisby, B. N. & Martin, M. M. (2010) Instructor-student and student-student rapport in the classroom. Communication Education, 59(2), 146-164. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/03634520903564362

Greer, M. & Harris, H. S. (2018). User-centered design as a foundation for effective online writing instruction. Computers & Composition, 49, 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.05.006

Griffin, J. & Minter, D. (2013). The rise of the online writing classroom: Reflecting on the material conditions of college composition teaching. College Composition and Communication, 65(1), 140-161. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43490811

Miami University (2019). eLearning Miami. Miami University. https://miamioh.edu/academics/elearning/index.html

Paull, J.N. & Snart, J. A. (2016) Making hybrids work: An institutional framework for blending online and face-to-face instruction in higher education. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Reinheimer, D. A. (2005). Teaching composition online: Whose side is time on? Computers & Composition, 22(4), 459-470. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2005.08.004

Rodrigo, R. & Ramirez, C. (2017). Balancing institutional demands with effective practice: A lesson in curricular and professional development. Technical Communication Quarterly, 26(3), 314-328. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2017.1339529

Sapp, D. A. & Simon, J. (2005). Comparing grades in online and face-to-face writing courses: Interpersonal accountability and institutional commitment. Computers and Composition, 22(4), 471-489. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2005.08.005

Spinuzzi, C. (2005). The methodology of participatory design. Technical Communication, 52(2), 163-174. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43089196