Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Charlotte Asmuth |

| Original Publication Date: | 01 June 2021 |

| Permalink: |

<gsole.org/olor/ep/2021.06.01> |

Abstract

Think-aloud protocols (TAPs) involve people verbalizing their thought processes as they perform a particular task. When TAPs are recorded and revisited, they can offer insight into the strategies and thought processes writers, readers, or users bring to a particular task. This essay explores how TAPs were used to model metacognitive reading strategies in an online, intermediate college writing course. After describing how TAPs were used in English 102, the author provides advice for instructors wishing to incorporate TAPs in their courses.

Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Think-aloud Protocols and OLI Contexts

1.1. An Introduction

[1] Think-aloud protocols (TAPs, for short) involve people verbalizing their thought processes (literally, thinking aloud) as they perform a particular task––for example, testing a product, reading a text, or composing an essay. When TAPs are recorded and revisited, they can offer insight into the strategies and thought processes writers, readers, or users bring to a particular task. Originating in usability studies, and popularized in writing studies research by Flower and Hayes (1981; see also Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987; Emig, 1971; Smagorinsky, 1989), TAPs have been used to capture the complex, recursive, cognitive processes writers engage in as they compose.

I have used think-aloud protocols in 300-level research writing in the disciplines courses, 100-level face-to-face first-year writing courses, and an online, asynchronous first year-writing course. The online course, English 102: Intermediate College Writing, was delivered at a four-year, public research university through the institution’s LMS (Blackboard). Think-aloud protocols, however, can be used in a variety of other courses, such as business and technical writing courses. Think-aloud protocols can also be used by instructors in other disciplines to help make tacit knowledge and practices explicit for students.

1.2. Use-Value in OLI

[2] While TAPs have been used extensively in cognitive process writing research and some literacy teachers report using them in face-to-face classes (Coiro, 2011; Kymes, 2005), their pedagogical uses have been underexplored in online literacy instruction. Nevertheless, this practice is supported by research that emphasizes the importance of pedagogies that link reading and writing (e.g., Carillo, 2016; Hewett, 2015; Horning, Gollnitz, & Haller, 2017), as well as more recent scholarship in OLI (e.g., Hewett, 2015). While Beth Hewett does not discuss TAPs in her book Reading to Learn and Writing to Teach, she recommends the “[u]se of audio recordings of teachers and students both reading and writing” in her chapter on teaching reading strategies (p. 88). Similarly, Alice Horning suggests that teachers “teach critical reading strategies” by, for example, “read[ing] a portion of an assignment aloud to students and explain[ing] the thought process involved while moving through the text” (2017b, p. 90).

[3] OLI educators, notably Hewett (2015), recommend that OLI instructors explicitly teach metacognitive reading strategies. Teachers’ recorded think-aloud protocols provide students with demonstrations of the metacognitive strategies that experienced readers use, including

- scanning, previewing, and otherwise attending to the organization of a text (Bazerman, 1985; Hillesund, 2010; Horning, 2011; Horning, 2017b, p. 89; Shanahan et al., 2011)

- reading rhetorically (Haas & Flower, 1988; Shanahan et al., 2011)

- making connections to other texts or experiences (Bazerman, 1985; Hillesund, 2010; Shanahan et al., 2011)

- making predictions and revising those predictions as they read (Bazerman, 1985)

- raising questions (Carillo, 2016, p. 19; Shanahan et al., p. 418)

- and annotating (Hillesund, 2010; Horning, 2011).

[4] TAPs give students “live” examples of how an experienced reader navigates a challenging text, and TAPS make normally silent, tacit reading behaviors explicit and available for reflection. For example, after viewing a TAP like the one shared below, students are often surprised that I do not read a text in a linear manner but instead approach it recursively. They then reflect on when it might be useful for them to use this reading strategy.

2. Negotiating Reading Challenges in OLI

[5] That college students struggle with reading academic texts is well-documented (Haas & Flower, 1988; Horning, 2017a, pp. 7-13; Jamieson, 2013; Jolliffe, 2007). I have found that students’ reading difficulties are exacerbated in online courses, where the literacy load is higher (Griffin & Minter, 2013, p. 153; Hewett, 2015, pp. 169-171; Warnock, 2009) and students lack the frequent interactive contact with teachers and students that a face-to-face course affords. While Discussion Board conversations and digital annotation platforms provide venues for sharing reading strategies and troubleshooting, they are not as helpful for demonstrating the reading strategies that experienced academic readers use. To that end, in online literacy instruction contexts, teachers can record TAPs to

- model complex reading and writing processes in-the-moment for students,

- illustrate readers’ social and cognitive processes,

- and help students hone their abilities to anticipate readers’ expectations in their writing.

[6] I’ve found TAPs especially helpful for modeling reading strategies for students early in the semester. The first three weeks of my first-year writing course are devoted to having students reflect on their existing reading strategies, read about and test new reading strategies, and compare their annotation habits to their peers in a digital annotation platform (see Praxis Snapshot 1 below for a sample activity). At some point during the first third of the semester, as the course texts start to get more challenging, I record and share a TAP as I interact with a research article.

Praxis Snapshot 1: Assignment Prompt: Testing Reading Strategies

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF ASSIGNMENT PROMPT (OPENS GOOGLE DOCS IN NEW WINDOW)

3. How To Implement: An Example, Practical Advice, and Required Materials

3.1. An Example

[7] Broadly, the goal of the TAP that I describe below is to model reading strategies for students that they then try out on our course texts. Early in the semester, when students need help adjusting to the literacy load and the challenging nature of some of the course readings, instructors can record a short think-aloud protocol of themselves engaging with part of a challenging course text. Video 1 is a think-aloud protocol that I recorded for students. Before I provide some technical guidance and practical recommendations for implementing TAPs, I want to describe what students learn from this activity.

[8] In this sample TAP (Video 1), I read the text aloud, pausing to report what I’m taking away from the text, when I’m struggling with an aspect of the reading, and how I’m dealing with that difficulty. I have adopted the disposition of an engaged (though not expert!) reader for this video in order to model strategies that I hope students will start to use. For example, I deliberately research the article’s place of publication before I start reading. In the video, I demonstrate the following reading strategies, which experienced readers employ (see esp. Horning, 2011, on the effectiveness of these strategies):

- making predictions and confirming/revising them as I continue to read

- reading rhetorically (e.g., researching the place of publication)

- attending to the structure/organization of the text

- tracking my questions (about the writer’s key terms)

- making connections to prior knowledge/other sources

- attending to the writer’s work with sources

- and attending to linguistic cues (e.g., signposting).

[9] The above strategies are part of a complex set of cognitive processes involved in reading. Modeling these strategies may do more than improve students’ reading behaviors. Sociocognitive studies have found that improving students’ reading behaviors can also improve their writing abilities (see Shanahan, 2016, for a review of this literature).

[10] Once students have viewed my TAP, I give students the opportunity to reflect in writing about what they notice me doing in the TAP. This can be done in an email or a Discussion Board conversation, journal entry, or other format in the LMS. For the Video 1, the following questions guided students’ reflections: “What kinds of reading strategies did you notice me using in the video? How might you use these strategies as you read sources for your project this week? Did anything surprise/not surprise you about the way in which I navigated the reading? What difficulties did you notice me encountering as I read? How did I work through those difficulties?” Praxis Snapshot 2 offers more detailed scaffolding.

Praxis Snapshot 2: Assignment Prompt: Respond to a TAP

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF ASSIGNMENT PROMPT (OPENS GOOGLE DOCS IN NEW WINDOW)

[11] After watching this video, my students have been quick to notice me using the above reading strategies. Some express surprise to hear me previewing/skimming for structural cues (because they assume readers read a text from beginning to end). Others express surprise at how many details I remember about our course texts as I’m reading. (One student commented that he normally tries to note connections to other texts after he has finished reading, but he now realizes it would be more useful to do so as he reads.) And several students are surprised to see me research the place of publication. They comment that this is a habit they would like to adopt, too. One student noticed how I was patient with myself when I didn’t immediately understand something. She wrote that, instead of giving up or getting frustrated when she doesn’t understand, she wants to practice reassuring herself when she reads challenging texts. After viewing and reflecting on my TAP, students shared new insights on the importance of annotating as they read. Several students wrote about how they now understood the importance of noting questions and paraphrasing particular ideas in the margins of a text, indicating that they saw annotation as a way to record their thinking as they read.

[12] After students have viewed and reflected on my TAP, I ask students to try out the reading strategies they notice me using on the sources they read for a writing project.

3.2. Practical Advice

[13] Instructors who want to use TAPs in OLI contexts might find the following recommendations helpful:

- Keep in mind the context of your course and your students’ needs. The reading strategies you model in your TAP may differ for 100-level and 300-level courses. For example, for a 300-level course, I might demonstrate how I usually begin reading academic articles by turning to the reference page to see what scholarly conversations the article is grounded in. For a 100-level course, I’ll instead demonstrate how I pay attention to the headings in an article, treating them as signposts for what’s to come. But no matter the course, whenever I do TAPs for students, I try to anticipate the difficulties students are likely to encounter when they read and to model strategies for working through those difficulties. I want students to expect to encounter challenges when they read.

- Be mindful of the teacher/student power dynamic, and its potential to influence what students write in response to your TAPs. This power dynamic may make students less likely to critique your reading strategies or less likely to express confusion about why you’re using a particular reading strategy. My students have mostly reacted to my TAPs with a mixture of surprise and curiosity rather than discomfort. This may be because I’m not so much reading like an “expert,” but rather reading like an engaged reader who has a little bit more experience than they do. For example, I ask questions that I already know the answers to as I engage with the text in the hopes that students will start to ask questions as they read, too.

- Draft a rough script to capture the gist of what you’ll say. Skim the text you’ll be working with and jot down a few notes next to where you plan on stopping and thinking-aloud as you read. This way, you won’t feel pressure to pause and report your thinking after every single sentence, which might lead you to produce a very long video and overwhelm students.

- Explain to students what a TAP is and why you’re recording one. I’ve done this at the beginning of the sample assignment prompt. This can also be done verbally at the beginning of a TAP recording. This context will help students get more out of your TAP.

- Speak slowly and pause often. You want students to be able to take notes in response to your protocol so that they can use what they’ve learned.

- Record your TAP and make it available for the entire semester on the LMS. The advantage of the recorded TAP is that students can revisit it throughout the semester on their own or prompted by you, the instructor, if you notice that students are struggling with a new reading.

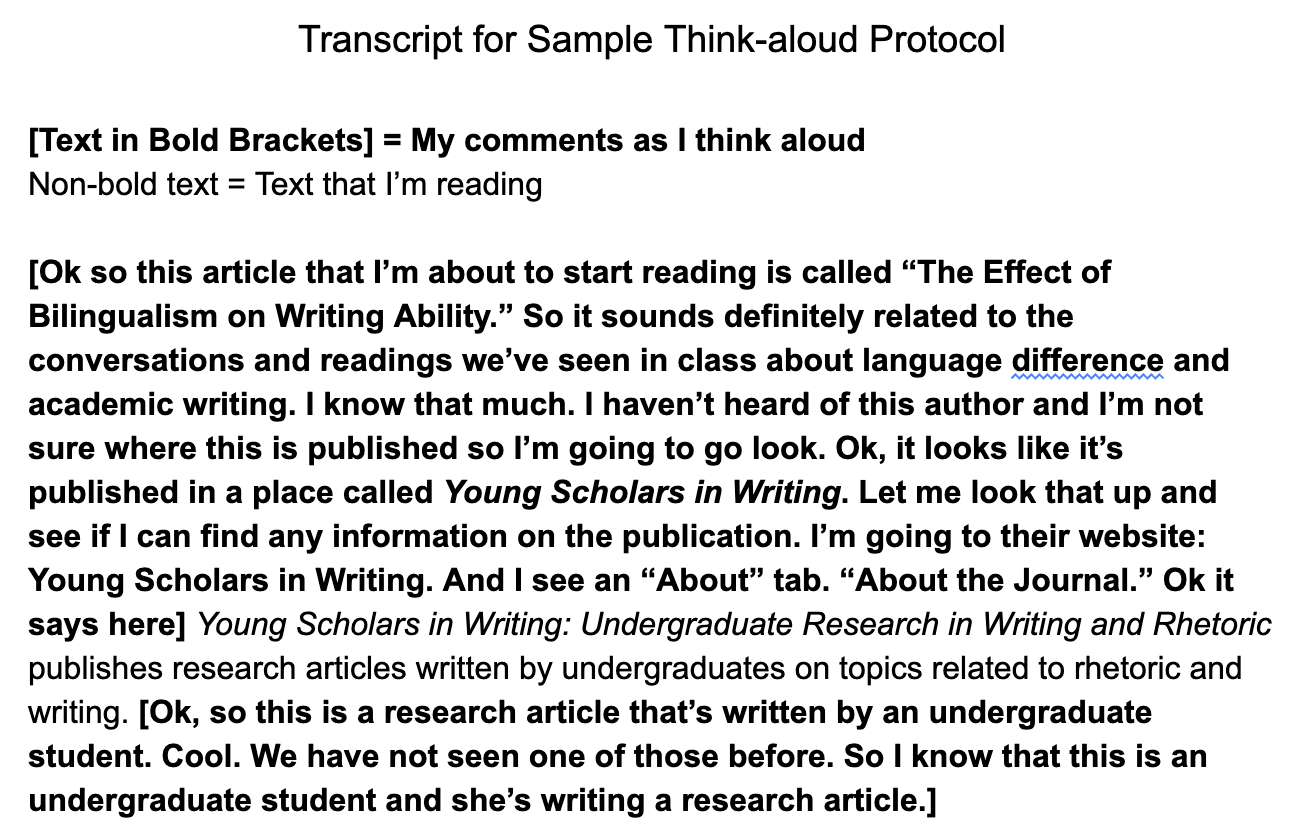

- Include a transcript of your TAP that clearly distinguishes between the text you read and your responses to that text. Praxis Snapshot 3, for example, is the transcript for the sample video I’ve included. This provides students with another way to access and study the TAP.

[14] While I’ve focused here on using TAPs to model metacognitive reading strategies, there are, of course, other ways to use TAPs in OLI contexts. For instance, instructors can use TAPs to model strategies for locating information online (see Coiro, 2011, for two sample lessons and TAPs). Teachers who are interested in having students conduct TAPs with each other’s writing will find Janet Giltrow et al.’s (2014) book helpful (see pp. 81-108).

Praxis Snapshot 3: Transcript for TAP

ACCESS TRANSCRIPT OF ASSIGNMENT PROMPT (OPENS GOOGLE DOCS IN NEW WINDOW)

3.3. Required Materials

[15] Instructors will need an audio-recording device. A webcam, which is generally built into most computers, can be used if instructors want students to be able to see them. In Blackboard, the following tools can be used to record TAPs: Blackboard Collaborate Ultra, the video conferencing system native to Blackboard, or a tool like VoiceThread, which is a stand alone platform though there is a Blackboard integration available. Instructors can also use open source tools like QuickTime (which does not have a recording time limit and is built in to most Mac computers), Screencastify (which has a five-minute time limit per recording for the free version) or Screencast-O-Matic (there is a fifteen-minute time limit per recording for the free version). The recordings can be easily uploaded to Google Drive and/or YouTube.

4. References

Bazerman, C. (1985). Physicists reading physics: Schema-laden purposes and purpose-laden schema. Written Communication, 2(1), 3-23.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Carillo, E. C. (2016). Creating mindful readers in first-year composition courses: A strategy to facilitate transfer. Pedagogy, 16(1), 9-22.

Coiro, J. (2011). Talking about reading as thinking: Modeling the hidden complexities of online reading comprehension. Theory into Practice, 50(2), 107-115.

Emig, J. (1971). The composing processes of twelfth graders. National Council of Teachers of English.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. College Composition and Communication, 32(4), 365-387.

Giltrow, J., Gooding, R., Burgoyne, D., & Sawatsky, M. (2014). Academic writing: An introduction (3rd ed.). Broadview Press.

Griffin, J., & Minter, D. (2013). The rise of the online writing classroom: Reflecting on the material conditions of college composition teaching. College Composition and Communication, 65(1), 140-161.

Haas, C., & Flower, L. (1988). Rhetorical reading strategies and the construction of meaning. College Composition and Communication, 39(2), 167-183.

Hewett, B. L. (2015). Reading to learn and writing to teach: Literacy strategies for online writing instruction. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Hillesund, T. (2010). Digital reading spaces: How expert readers handle books, the web, and electronic paper. First Monday, 15(4), firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2762/2504.

Horning, A. S. (2011). Where to put the manicles: A theory of expert reading. Across the Disciplines, 8(2), wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/articles/horning2011.pdf.

Horning, A. S. (2017a). Introduction. In A. S. Horning, D-L. Gollnitz, & C. R. Haller (Eds.), What is college reading? (pp. 3-18). The WAC Clearinghouse.

Horning, A. S. (2017b). Neuroscience of reading: Developing expertise in reading and writing. In P. Portanova, J. M. Rifenburg, & D. Roen (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on cognition and writing (pp. 79-94). The WAC Clearinghouse.

Horning, A. S., Gollnitz, D-L., & Haller, C. R. (Eds.). (2017). What is college reading? The WAC Clearinghouse.

Jamieson, S. (2013). Reading and engaging sources: What students’ use of sources reveals about advanced reading skills. Across the Disciplines, 10(4), wac.colostate.edu/docs/atd/reading/jamieson.pdf.

Jolliffe, D. A. (2007). Review essay: Learning to read as continuing education. College Composition and Communication, 58(3), 470-494.

Kymes, A. (2005). Teaching online comprehension strategies using think-alouds. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 48(6), 492-500.

Shanahan, T. (2016). Relationships between reading and writing development. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed.) (pp. 194-207). The Guilford Press.

Shanahan, C., Shanahan, T., & Misischia, C. (2011). Analysis of expert readers in three disciplines: History, mathematics, and chemistry. Journal of Literacy Research, 43(4), 393-429.

Smagorinsky, P. (1989). The reliability and validity of protocol analysis. Written Communication, 6(4), 463-479.

Warnock, S. (2009). Teaching writing online: How and why. National Council of Teachers of English.