Publication Details

| OLOR Series: | OLOR Effective Practices |

| Author(s): | Bonnie McLean |

| Original Publication Date: | 22 FEBRUARY, 2024 |

| Permalink: |

<olor/ep/2024.02.22> |

This piece was authored as part of a GSOLE Research Fellows grant which is supporting authors as they adopt, implement, and collect data on an existing teaching practice published in the Online Literacies Open Resource “Effective Practices” (OLOR EP) journal.

McLean’s article is an extension of and response to “Supervising Team Projects Effectively in an Online Writing Course,” by Theresa M. Evans, published in OLOR Effective Practices (3 March 2021): https://gsole.org/olor/ep/2021.03.10

Readers are invited to consult the original article for a full discussion of Evans’ approach to managing team projects in OWI contexts, but for quick reference, the abstract to that article is here:

Team projects are always difficult to supervise, but online courses present unique challenges: The instructor has limited opportunity for real-time observations of and interactions with student teams, as they collaborate virtually in digital spaces. Still, virtual collaboration is an important skillset to develop, given that distributed teams are becoming more common in the workplace. Team projects in online courses create—for both instructors and students—a double burden of working with subject content and developing successful strategies for virtual communication and work processes (Paretti et al., 2007, p. 331). I encourage a layered approach to teamwork through my efforts to scaffold—to structure—team projects in online writing courses. Students have ongoing scheduled check-ins with me, which they can use as a starting point for their more detailed team schedule. These check-ins include at least one synchronous meeting and a combination of individual and team assignments that build towards the final deliverables.

- Jason Snart, OLOR EP founder and editor

Abstract

To mitigate negative self-perceptions related to team-oriented projects in online writing courses, I adapted a layered approach presented in Theresa Evans' (2021) “Supervising team projects effectively in an online writing course.” Evans’ implementation of the layered approach to team building has illustrated the need for equal partnerships between a student, the instructor, and their peers, independent of the instructor. Deviating from Evans’ use of a synchronous meeting as part of the project, I emphasized a fully asynchronous process. Yet this adaptation did not facilitate the trust that Evans and other scholars argue is necessary for true collaboration within online writing courses. Consequently, I realized my own need for a more explicitly responsive model to asynchronous project building, as well as a more comprehensive timeline for student trust-building, communication, and project creation.

Resource Overview

Resource Contents

1. Introduction

[1] As a student motivated by self-imposed high standards and the desire to earn the best grade possible, I balked at group projects and saw them as an uneven collaborative endeavor between peers. I carried this negative attitude into my instruction of both synchronous and asynchronous courses until reading Theresa Evans’ (2021) “Supervising team projects effectively in an online writing course.” Evans’ implementation of a layered approach to team building illustrates the need for equal partnership, not just between student and teacher—as is often the case in Online Writing Instruction (OWI)—but between the students themselves. After reading Evans’ article and introducing a variation of her layered approach—a team-building model which emphasizes differentiated group roles to distribute labor equitably for project completion—I now recognize the need for collaborative partnerships between instructor and students, particularly in asynchronous modalities.

[2] As part of her layered approach to team building, Evans (2021) includes at least one synchronous meeting between teams and the instructor in the process. I varied my approach by having the professor oversee a completely asynchronous process and encouraged students to formulate their own modes of communication within group-specific modules in Blackboard, our institution’s Learning Management System (LMS). Consequently, I realized my own need for a more explicitly responsive model to asynchronous project building, as well as a more comprehensive timeline for student trust-building, communication, and project creation.

Context

[3] I implemented my variation on Evans’ (2021) layered approach to team building in the Spring 2023 semester at College of DuPage (COD) in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, which is located in DuPage County, about 30 miles west of Chicago. COD is a two-year community college that in Fall 2022 saw a total enrollment of 21,939 students, 11,777 were enrolled full-time for coursework. Forty-six percent (46%) of these students intend to transfer to other institutions, and forty-two percent (42%) returned from the previous semester. Eighty percent (80%) of the total headcount resided within the district, 41% spanned 19-24 in age, and 45% of students identified as White, with the second-largest category identifying as Latinx (26%). Overall, COD serves as a transition point for local students seeking entry at four-year institutions, with a minority seeking programs or educational opportunities from within the institution (College of DuPage, n.d.). While COD boasts a wide variety of students from different demographics within a shared region, I had to reconfigure a shared identity from a face-to-face classroom to one that would develop with my students’ presence and values they brought to the course.

[4] As an institution matriculated into the Illinois Articulation Initiative (IAI), COD’s English Department offers a two-pronged Composition sequence, with each course spelling out course objectives that allow for transferability of the courses between IAI-compliant institutions. English Composition I focuses on student-centered writing and rhetoric, whereas English Composition II focuses on writing and rhetoric in research. Despite the individualized focus of research rhetoric, I intentionally chose English Composition II for a layered approach, to foster a spirit of collective learning and engagement across disciplines and majors.

2. Methods

[5] My pedagogical foundations for the team-built project originated with Evans’ (2021) article, particularly the notion of trust. I realized that my model of OWI had been highly individualized and was therefore not conducive to the trust-building required of a team exercise. I took Evans’ injunction seriously about formative exercises to create that trust:

Trust is an important aspect of successful collaboration, which can only develop if team members get to know each other. In my technical writing course, team projects come in the second half of the semester, and by then, ideally, students are already familiar with each other through discussion forums and peer responses, if not synchronous meetings. (Evans, 2021, para. 20)

One of the most crucial aspects of a trust-built asynchronous course is the social presence that undergirds interactions between students who do not see each other in a physical space. Corroborating Cunningham, et al (2022), note, “Traditionally understood, social presence purports that online and hybrid classes must establish a feeling of collaboration, belonging, or trust in order to create a true community of learning” (para. 10). Therefore, in order to cultivate a successful group project, I needed to build student-to-student trust through formative exercises that would lead up to the culminating project.

[6] I first reexamined my course design to facilitate trust among students and build both formative and summative assessments that would promote such trust. In my online courses, I always include asynchronous peer review and discussion forums, but for my Spring 2023 courses I added informal wikis as a way to introduce students to collaborative knowledge-building. Since Blackboard includes a wiki builder as part of its platform, I decided to use the tool readily available to the students. As part of building trust among members of the classroom discourse community, I wanted to align with Principle 1 of the Global Society of Online Literacy Educators' Online Literacy Instruction Principles and Tenets (Warnock, et al., 2019), which states, “Specifically, students should not need to learn extraneous technology in order to meet the course objectives; teachers should not need to learn and teach extraneous technology when the LMS will suffice." In retaining the structured platforms and materials, I hoped that increased familiarity with content and technology would give students increased mental energy to establish trust in each other and the collaborative process without adding an additional learning objective.

[7] I assigned the culminating group project in the fourth and final unit before our final exam, so that students could spend the semester interacting with each other in low-stakes group discussions and peer review. Before beginning our collaborative unit and while using weekly activities to prepare students for their joint project, I linked a Google Form to our Blackboard weekly folder during Unit 3 to ascertain students’ work style, topic preferences, and comfort with each other. Each of the following topics modeled the research process and the work students had conducted individually, so having to write a wiki entry on that portion of the process allowed them a chance to share in knowledge building with me and each other. I downloaded a table of student responses, so that I could formulate my own spreadsheet of their interests and try to keep their content preferences in mind. Since students could self-select their research topics for the semester, I wished to honor their individual choices in the context of a team-built project as well.

[8] Beyond choice in content, I empowered students to build a desired team, based on shared interests or values. The survey included a question about their preferences in building their team, based on whether they held a shared work style or shared interest in the topic. While I recognized that the relative anonymity of the personal request might have been a constraint to students’ choices, I hoped that the cumulative forums, peer feedback workshops, and wiki-building would allow students a chance to get to know others in an online “classroom.” Therefore, I enabled the self-selection process with curiosity about its efficacy in asynchronous spaces.[9] During the unit, I tried to follow Evans’ (2021) layered approach of collaboration, beginning with forums where students had to introduce themselves to each other asynchronously. As with each unit, students embarked on forums and discussions, while also practicing collaborative writing in a wiki I set up. And as with previous units, I conducted an asynchronous review of their projects, where students submitted their rough drafts to a private blog, and I then provided feedback for their questions. This time, I set the blog up as a group submission so that the students could ask their questions individually and see each other’s questions and my responses.

[10] I deviated most from Evans’ (2021) layered model during this review. Evans made a strong case for a synchronous video conference “to help address concerns and clear up misunderstandings” (para. 38). I determined not to hold these synchronous video conferences, due to the unit’s relatively short length, and to ascertain whether I could build trust in a course that was totally asynchronous, as many colleges require of their OWI and instructors. As Snart (2015) asserts, “In the strictest sense of the OWI environment, requiring onsite meetings means that the learning no longer is fully online, and using this terminology not only may confuse students and teachers but likely will limit access to some” (p. 108). Because an increasing number of students in my online writing courses (OWC) have self-disclosed childcare difficulties, enrollment at other institutions, work responsibilities, or a combination of the above, I wanted to retain an equal level of access for my groups.

[11] I then gathered student feedback to assess their perceptions of the unit’s success from an individual and team standpoint, as well as my supervision of the team projects. I created a post-unit inventory survey using a Google Form, to ascertain whether I had successfully built the trust required for students to work together and with me in an equitably collaborative partnership. Students had to answer questions about their satisfaction with the project, successes, room for improvement, expected grade, and assessment of their peers’ contributions. Students viewed the survey before the project began, so that they would know how they would evaluate themselves and their teammates. To ensure accountability, I reminded students that the inventory would be an individual component of their project grade over which they had complete control, and I included links in the weekly folder, the project description sheet, and the dropbox submission folder itself.

3. Results

[12] All the final wiki entries in both courses showcased satisfactory information, formatting, advice, and resources. The surveys themselves all displayed similar individual expectations of their grades and performance, but diverged when it came to assessment of their teammates and advice to the professor. Entering the unit, I anticipated about 5-6 students in each course of 18 would not respond to the survey, and a portion of that number would not participate in the project at all, so I was pleased by the overall number of responses to the survey (see Table 1). I tried to distribute students evenly between those who participated and those who remained largely absent from the course, so that all groups had at least two active members.

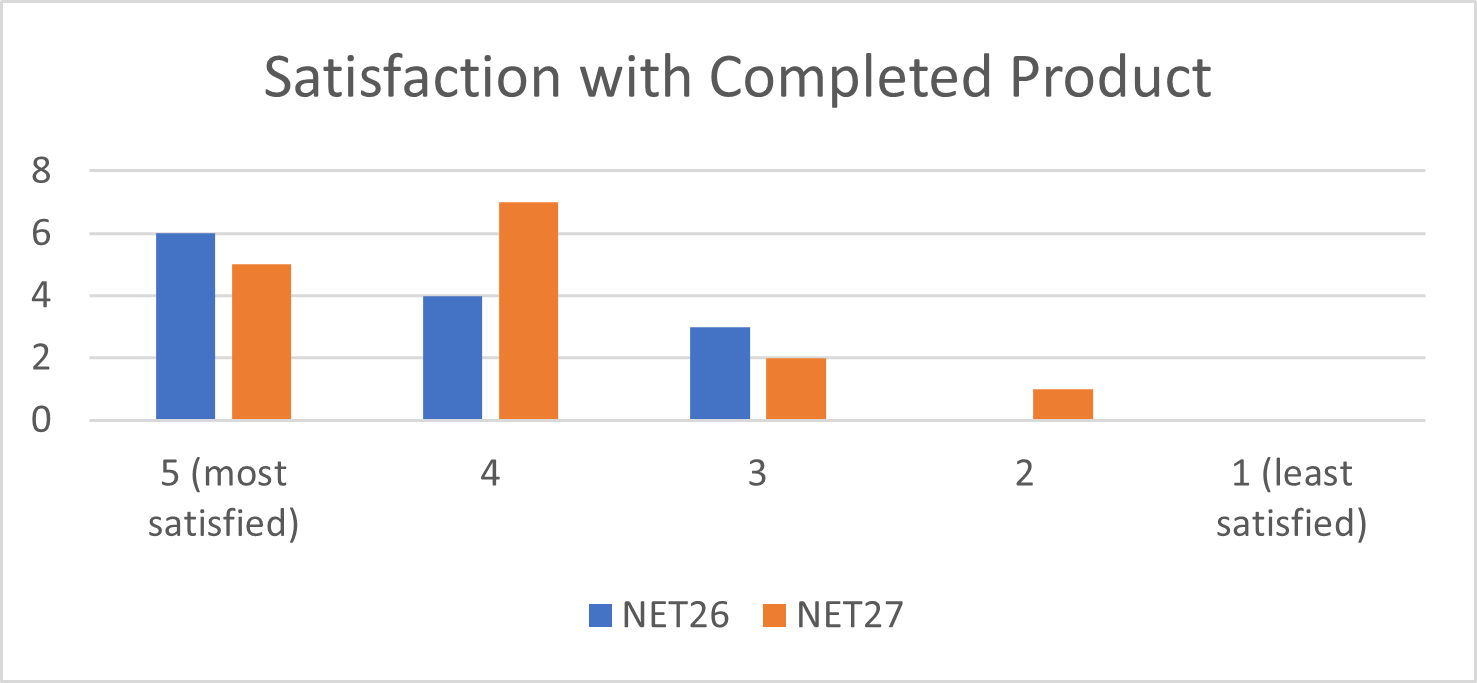

[13] In their responses, students had to self-assess their satisfaction with the final project. I was curious with their reflections on the project and pleased by their conclusions. The following figure denotes students’ self-reported satisfaction with the project (see Figure 1).

[14] As we can see, despite my own reservations about team-constructed projects, my own students reported a high level of satisfaction with their finished work. Even with obstacles reported on the survey, most of the students in each course found a way to succeed with the final project. I was glad that the preparatory survey I had administered gave students the opportunity to provide their preferences. Allowing students to indicate their preferences in topic and teammate enabled them to retain a sense of choice and self-determination in a team project.

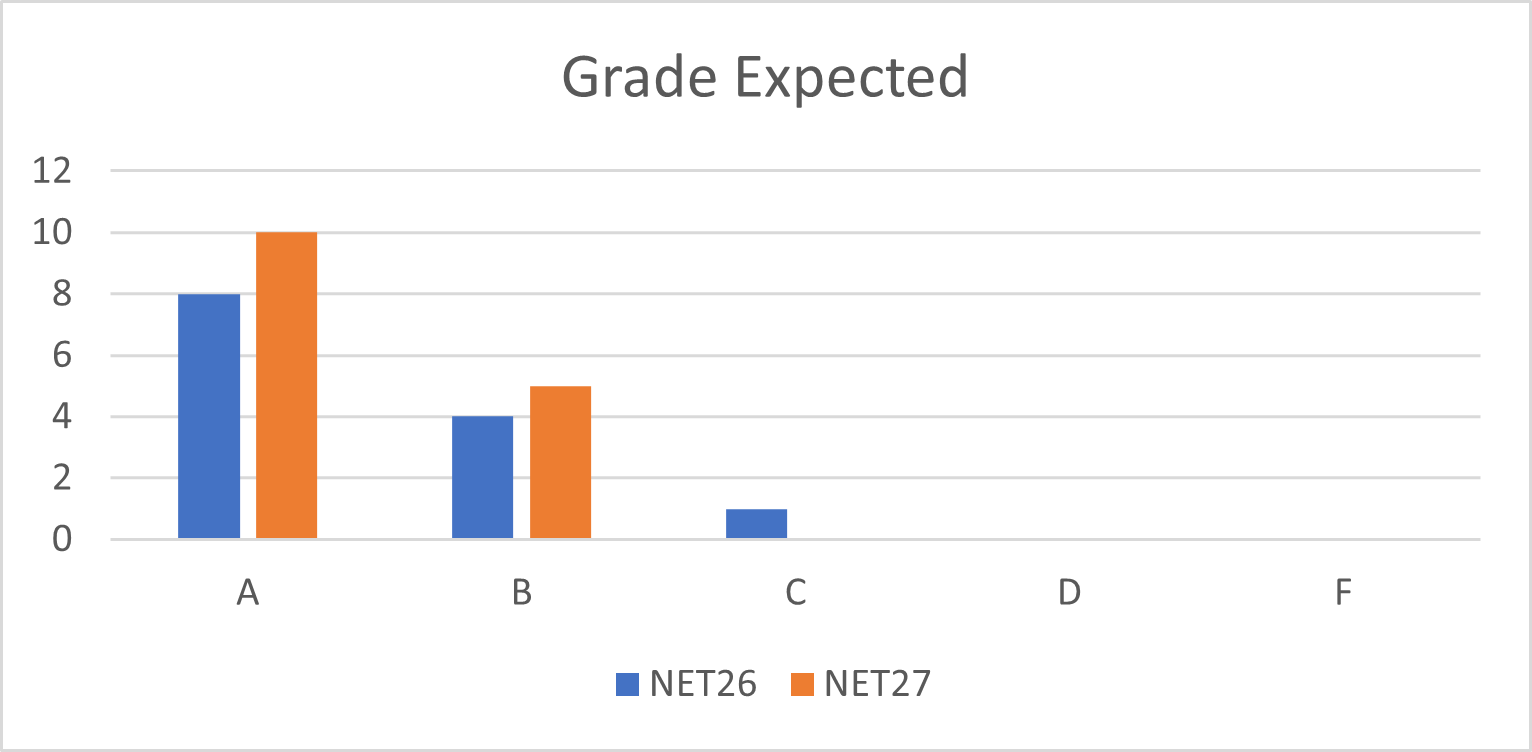

[15] While assessing the projects, I was curious to see how students felt they had done before receiving their final grades. I was glad that so many students expressed confidence in the final project and their contributions to it. The anticipated grades, therefore, mirrored their self-trust. The following figure denotes student expectation of the grade they would receive, before I had graded their projects (see Figure 2):

[16] Again, we can see that students expected their work to succeed, whether through individual or collective effort. Because most of the students received an A on the project, notwithstanding the survey, they seemed aligned with their own expectations of the product and how I would perceive it.

[17] In their feedback, students presented a common challenge in communication, particularly with peers who lacked consistent presence in the course. As one student noted, “I think my group did not work too well together. It took a week and a half to get a hold [sic] of my team and set up a meeting and only one of them joined while the other one barley [sic] replied throughout the process.” This student’s frustration echoed my own fears that students who did not log into the course and demonstrate equal engagement would benefit from their peers’ efforts. Frustration arising from inequitable division of labor did not hold true for all groups, however, as students also explained how they overcame those obstacles—student comments included making changes to assignments, or modifying final entries to match their current group efforts.

[18] As I also suspected, synchronous meetings proved challenging due to a variety of needs and schedules. One student asserted, “I think we worked well together, again the actual communication was good, and we collaborated well, but it was hard at times as we all have different schedules waiting for each other to respond which is understandable.” This difference in schedule again came up with another student’s feedback: “I felt my group worked together pretty well. It was sometimes hard to communicate with each other or get one to answer on time. Everyone listened to each other's ideas so that was good.” Here, the student couched the challenge in a statement of praise of their group, so that even if the timing was poor, the communication itself was effective when it took place. This student’s assertion also illustrates yet again why students choose asynchronous online courses, despite perceived challenges or lack of community: the ability to fit courses into an otherwise busy schedule.

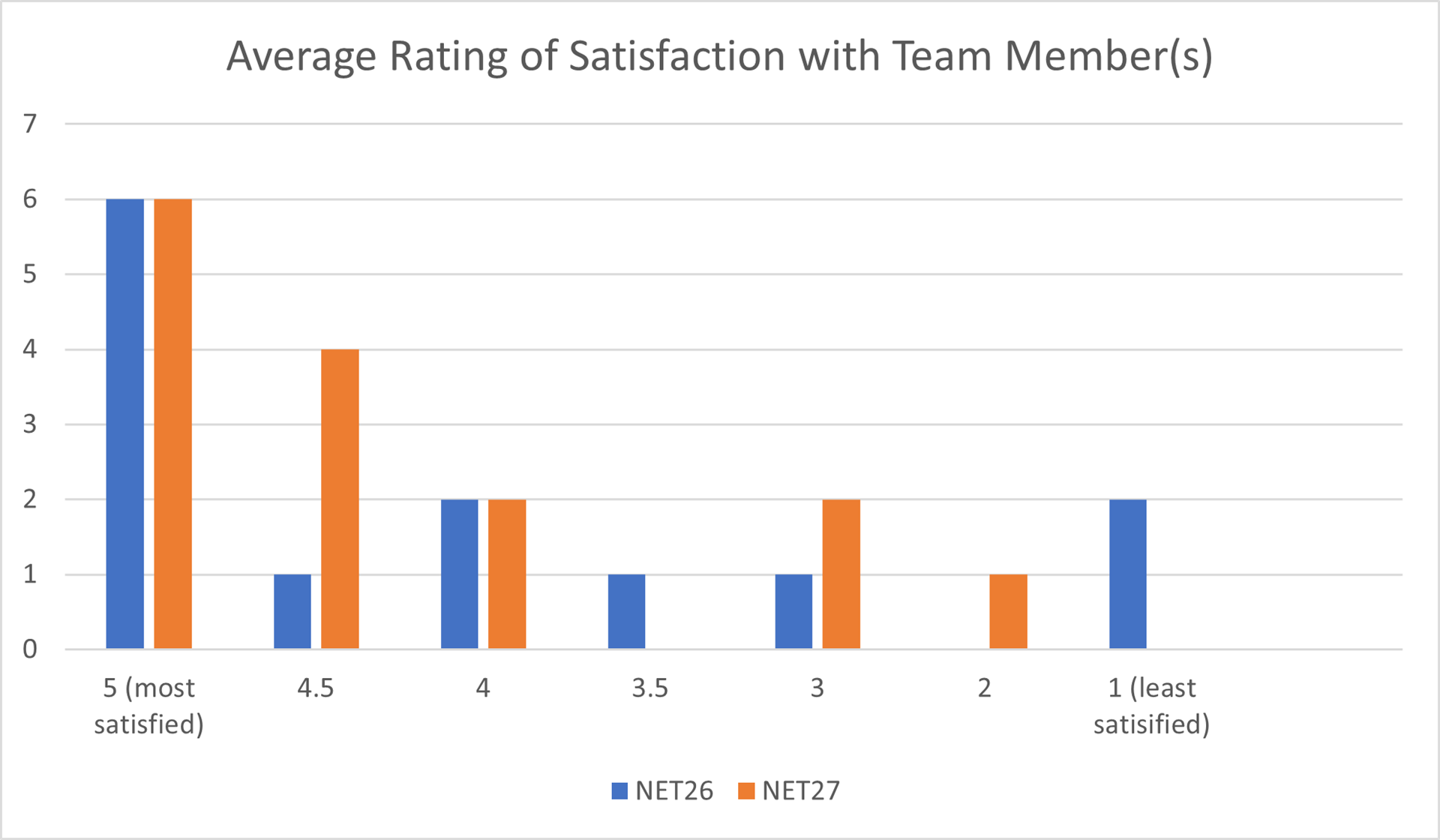

[19] The students surprised me in their overall positive assessments of their teammates. I compiled an aggregation of their ratings of each other and noted that their satisfaction with their classmates adhered relatively closely to their self-assessment. The following figure shows how students assessed their peers, whether they formed a group of two or three (see Figure 3):

[21] The most variance in student feedback emerged in their recommendations to me as the professor. Several recommended better visual samples so that they could more accurately format and build a representative wiki. Others advocated for a synchronous meeting. One student suggested, “To improve it I would maybe have a zoom call and put the groups into breakout rooms and the professor can go to each group and answer questions if needed or check on the status of the group.” While I commend the student’s specificity, the suggestion presents difficulty for instructors whose colleges enforce a strict asynchronous structure in their OWC’s.

[22] Ultimately, I believe that the breakdowns in communication between team members stems from my logistics in planning, feedback distribution, and team building. When defaulting to a team-only mode of communication and failing to hold myself accountable in a Community of Inquiry, I missed out on an opportunity to help students individually, particularly those who were struggling to maintain presence in the course. As Borgman and McArdle (2019) asserted, “Part of [...] individualized teaching includes building a relationship with each individual student in your course. Students need to build a relationship of trust with you as their instructor because they are sharing something very personal with you: their writing” (p. 60). In varying my approach from Evans’ (2021), I did not allot myself enough time to be able to adhere to her layered approach as a mode of building trust between my students and me. I could have further inculcated trust between students through a variety of methods, including individual feedback or a group email between me and the students.

Looking Forward

[23] In order to more closely adhere to Evans’ (2021) layered approach, I need to examine those layers more intentionally and make sure students have enough time to move through all the levels of the project, from creation to collective crafting of their work. . I instituted the concept of “team meetings” as a check-in for students, but I did not give them enough time to communicate with each other and with me. Evans modeled a six-week schedule, which doubled my pace of three weeks. The extra time would have afforded the opportunity for students to communicate with me and each other more openly and on a more flexible schedule than a tighter schedule permitted.

[24] I will be teaching English Composition II in Spring 2024, andI have determined to reconcile Evans’ (2021) recommendations with my own convictions about retaining a fully asynchronous course. From these findings, I will again supervise an asynchronous team-building project but include several revisions. First, I have implemented formative team-building exercises in my Fall 2023 English Composition I courses, to help students build trust with each other. I use a “lab” weekly activity, where students must introduce themselves to each other, take on the role of the “researcher” (who gathers data) or the “analyst” (who evaluates the findings), and then contribute to the components of the activity asynchronously, while also analyzing results and asking questions. Another revision I will employ is a longer timeframe for the group project, perhaps occurring concomitantly with other assignments. This way, students will have the time to get to know me individually and each other as peers, so that the team-building and communication can grow slowly throughout the semester.

[25] Finally, I plan to showcase technology built within the LMS, as well as Google Suite programs. To better foster student engagement with each other and me, I will provide video tours of the in-course technology provided for the students, including a group blog, document-sharing capabilities, and a private wiki. Encouraging the use of document sharing through Google Suite tools will facilitate communication, and also allow flexibility for students with differing schedules.

4. Conclusion

[26] Supervising team projects has taught me an exercise in trust. By granting my students more opportunity to trust me, they can then learn how to trust each other. By trusting my students’ experience and ideas, I can better facilitate communication and encourage them to manage their own project deadlines. Ultimately, learning to better supervise team projects asynchronously will give me the tools to help my students in future professional scholastic or career endeavors.

7. References

Borgman, J., and McArdle, C. (2019, October 23). Personal, accessible, responsive, strategic: Resources and strategies for online writing instructors. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/PRA-B.2019.0322

College of DuPage Administration. (n.d.) Planning, reporting, and financial documents. College of DuPage, https://www.cod.edu/about/administration/planning_and_reporting_documents/pdf/student-demo.pdf

Cunningham, J.M., Stillman-Webb, N., Hilliard, L., and Stewart, M.K. (2022). Synchronicity over modality: Understanding hybrid and online writing students’ experiences with peer review. Composition Forum, 48, https://compositionforum.com/issue/48/synchronicity.php

Evans, T. (2021, March 10). Supervising team projects effectively in an online writing course. OLOR Effective Practices, https://gsole.org/olor/ep/2021.03.10.

Snart, J. (2015). Hybrid and fully online OWI. In B.L. Hewitt and K.E. DePew (Eds.), Foundational practices of online writing instruction. The WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2015.0650

Warnock, S., et al. (2019, June 13). OLI principles and tenets. Global Society of Online Literacy Educators, https://gsole.org/oliresources/oliprinciples.